- Home

- ABOUT US

- ABOUT VEYSEL BABA

- REDFOX ART HOUSE VIRTUAL TOUR

- MY LAST WILL TESTAMENT

- NOTES ON HUMANITY AND LIFE

- HUMAN BEING IS LIKE A PUZZLE WITH CONTRADICTIONS

- I HAVE A WISH ON BEHALF OF THE HUMANITY

- WE ARE VERY EXHAUSTED AS THE DOOMSDAY IS CLOSER

- NO ROAD IS LONG WITH GOOD COMPANY

- THE ROAD TO A FRIENDS HOUSE IS NEVER LONG

- MY DREAMS 1

- MY DREAMS 2

- GOLDEN WORDS ABOUT POLITICS

- GOLDEN WORDS ABOUT LOVE

- GOLDEN WORDS ABOUT LIFE

- GOLDEN WORDS ABOUT DEATH

- VEYSEL BABA ART WORKS

- SHOREDITCH PARK STORIES

- EXAMPLE LIVES

- ART GALLERY

- BOOK GALLERY

- MUSIC GALLERY

- MOVIE GALLERY

- Featured Article

- Home

- EXAMPLE LIVES

- Frida Kahlo

Frida Kahlo

Frida Kahlo de Rivera (Spanish pronunciation: [ˈfɾiða ˈkalo]; July 6, 1907 – July 13, 1954), born Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón, was a Mexican painter, who mostly painted self-portraits. Inspired by Mexican popular culture, she employed a naïve folk art style to explore questions of identity, postcolonialism, gender, class, and race in Mexican society. Her paintings often had strong autobiographical elements and mixed realism with fantasy. In addition to belonging to the post-revolutionary Mexicanidad movement, which sought to define a Mexican identity, Kahlo has been described as a Surrealist or magical realist. Her work has been celebrated internationally as emblematic of Mexican national and indigenous traditions, and by feminists for what is seen as its uncompromising depiction of the female experience and form.[1]

Born to a German father and a mestiza mother, Kahlo spent most of her childhood and adult life at her family home, La Casa Azul, in Coyoacán. She was left disabled by polio as a child, and at the age of eighteen was seriously injured in a traffic accident, which caused her pain and medical problems for the rest of her life. Prior to the accident, she had been a promising student headed for medical school, but in the aftermath had to abandon higher education. Although art had been her hobby throughout her childhood, Kahlo began to entertain the idea of becoming an artist during her long recovery. She was also interested in politics and in 1927 joined the Mexican Communist Party. Through the Party, she met the celebrated muralist Diego Rivera. They were married in 1928, and remained a couple until Kahlo's death. The relationship was volatile due to both having extramarital affairs; they divorced in 1940, but remarried the following year.

Kahlo spent the late 1920s and early 1930s traveling in Mexico and the United States with Rivera who was working on commissions. During this time, she developed her own style as an artist, drawing her main inspiration from Mexican folk culture and painting mostly small self-portraits, which mixed elements from pre-Columbian and Catholic mythology. Although always overshadowed by Rivera, her paintings raised the interest of Surrealist artist André Breton, who arranged for her to have her first solo exhibition at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York in 1938. The exhibition was a success and was followed by another in Paris in 1939. While the French exhibition was less successful, the Louvre purchased a painting from Kahlo, making her the first Mexican artist to be featured in their collection.

Throughout the 1940s, Kahlo continued to participate in exhibitions in Mexico and the United States. She also began to teach at the Escuela Nacional de Pintura, Escultura y Grabado "La Esmeralda", and became a founding member of the Seminario de Cultura Mexicana. Kahlo's always fragile health began to increasingly decline in the same decade. She had her first solo exhibition in Mexico in 1953, shortly before her death the following year at the age of 47.

Kahlo was mainly known as Rivera's wife until the late 1970s, when her work was rediscovered by art historians and political activists. By the 1990s, she had become not only a recognized figure in art history, but also regarded as an icon for Chicanos, feminists, and the LGBTQ movement.

Biography

1907–1924: Family and childhood

Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón[a] was born on July 6, 1907 in Coyoacán, then a village on the outskirts of Mexico City.[3]Kahlo stated that she was born at the family home, La Casa Azul (The Blue House), but according to the official birth registry, the birth took place at the nearby home of her maternal grandmother.[4] Kahlo's parents were photographer Guillermo Kahlo (1871–1941) and Matilde Calderón y González (1876–1932). Originally from Germany, Guillermo had immigrated to Mexico in 1891, after epilepsy caused by an accident ended his university studies.[5] Although Kahlo claimed that her father was Jewish, he was in fact a Lutheran.[6][7] Matilde was born in Oaxaca to an indigenous father and a mother of Spanish descent.[8] In addition to Kahlo, the marriage produced daughters Matilde (c. 1898–1951), Adriana (c. 1902–1968), and Cristina (c. 1908–1964).[9] She also had two half-sisters from Guillermo's first marriage, María Luisa and Margarita, but they were raised in a convent.[10]

Kahlo later described the atmosphere in her childhood home as often "very, very sad".[11] Both parents were often sick,[12] and Matilde's relationships with her daughters were extremely tense.[13] Kahlo described her mother as "kind, active and intelligent, but also calculating, cruel and fanatically religious".[13] Kahlo was close to her father, a man who often suffered from depression, but was praised by his daughter for his "tenderness" towards her.[14]Kahlo described the marriage of her parents as joyless and devoid of love[15] Furthermore, Guillermo's photography business suffered greatly during the Mexican Revolution of 1910–1920, as the overthrown government had commissioned works from him, and the long civil war limited the number of private clients.[12]

When Kahlo was six years old, she contracted polio, which made her right leg shorter and thinner than the left.[16][b] The illness forced her to be isolated from her peers for months, and she was bullied.[19] While the experience made her introverted,[11] it also made her Guillermo's favorite due to their shared experience of living with disability.[20]Kahlo credited him for making her childhood "marvellous ... he was an immense example to me of tenderness, of work (photographer and also painter), and above all in understanding for all my problems".[21] He taught her about literature, nature, and philosophy, and encouraged her to exercise and play sports to regain her strength after polio.[22] She took up bicycling, roller skating, swimming, boxing, and wrestling, despite the fact that many of these activities were then reserved for boys.[23] He also taught her photography, and she began helping him retouch, develop, and color photographs.[24]

Due to polio, Kahlo began school later than her peers.[25] Along with her sister Cristina, she at first attended the local kindergarten and primary school in Coyóacan, and was homeschooled for the fifth and sixth grades.[26] While Cristina went onto a convent school, their father enrolled Kahlo in a German school.[27] After being expelled for disobedience, she briefly attended a vocational teachers school.[26]Her parents took her out of the school when she embarked on an affair with one of her teachers, Sara Zenil.[26]

In 1922, Kahlo was accepted to the elite National Preparatory School.[28] The institution had only recently begun admitting women, with only 35 students out of 2,000 being girls.[29] Under the education minister, José Vasoncelos a new policy of promoting indigenismo had began as it was the policy of the government to promote un nuevo arte nacional that would give the Mexican people a new sense of identity as ordinary people were encouraged to celebrate Mexico's Indian heritage.{[30] Kahlo chose to focus on natural sciences with the aim of proceeding to medical school.[28] She performed well academically,[31] was a voracious reader, and became "deeply immersed and seriously committed to Mexican culture, political activism and issues of social justice".[32] Particularly influential to her at this time were nine of her schoolmates, together with whom she formed an informal group called the "Cachucas" — many of them would become leading figures of the Mexican intellectual elite.[33] They were rebellious and against everything conservative, and pulled pranks, staged plays, and debated philosophy and Russian classics.[33] To mask the fact that she was older and to declare herself a "daughter of the revolution", she began saying that she had been born on July 7, 1910, the year the Mexican Revolution began, which she would continue throughout her life.[34]

Kahlo enjoyed art from an early age, receiving drawing instruction from her father's friend, printmaker Fernando Fernández[35] and filling notebooks with sketches.[36] In 1925, she began to work alongside school to help her family.[37] After taking classes in typing and shorthand writing and briefly holding positions at a pharmacy, a lumber yard and a factory, she became a paid engraving apprentice for Fernández.[38] Although she did not consider art as a career during this time,[36] he was impressed by her talent.[39]

1925–1930: Bus accident, first paintings, and marriage to Diego Rivera

On September 17, 1925, Kahlo and her boyfriend and fellow Cachuca, Alejandro Gómez Arias, were on their way home from school when the wooden bus they were riding collided with a streetcar. Several people were killed, and Kahlo suffered nearly fatal injuries—an iron handrail impaled her through her pelvis, fracturing the bone. She also fractured several ribs, her legs, and her collarbone.[40][c] She spent a month in the hospital and two months recovering at home,[42] before being able to return to work to cover her medical expenses.[43] As she continued to experience fatigue and back pain in 1926, her doctors ordered x-rays, which revealed that the accident had also displaced three vertebrae.[44] Her treatment included wearing a plaster corset, which confined her to bedrest for several months.[44]

As well as ending Kahlo's dreams of becoming a doctor, the accident caused her pain and illness for the rest of her life; her friend Andrés Henestrosa stated that Kahlo "lived dying".[45] She started to consider a career as a medical illustrator, which combined her interests in science and art. To occupy herself during her recovery, she began to paint with an easel that made it possible for her to paint in bed. A mirror was placed above the easel so she could paint herself.[46] Painting became a way for Kahlo to explore questions of identity and existence,[47] and she later stated that the accident and the isolating recovery period made her desire, "to begin again, painting things just as I saw them with my own eyes and nothing more."[48]

Most of the paintings Kahlo made during this time were portraits of herself, her sisters, and school friends.[49] The preparatory school and the influence of her father, an amateur painter, had made her well-versed in art history. Her early paintings and correspondence show that she drew inspiration especially from European artists, in particular Renaissance masters such as Sandro Botticelli and Bronzino[50] and, avant-garde movements such as Neue Sachlichkeit and Cubism.[51]

Kahlo's bedrest was over by late 1927, and she began socializing with her old school friends, who were now at university and involved in student politics. She joined the Mexican Communist Party (PCM) and was introduced to a circle of political activists and artists — including the exiled Cuban communist Julio Antonio Mella, and the Italian-American photographer Tina Modotti.[52] At one of Modotti's parties in June 1928, Kahlo was introduced to Diego Rivera, one of Mexico's most successful artists and a notable figure in the Communist Party.[53] They had met briefly in 1922, when he was painting a mural at her school.[54] Shortly after their introduction in 1928, Kahlo asked him to judge whether her paintings showed enough talent for her to pursue a career as an artist.[55] Rivera recalled being impressed by her works, stating that they showed, "an unusual energy of expression, precise delineation of character, and true severity ... They had a fundamental plastic honesty, and an artistic personality of their own ... It was obvious to me that this girl was an authentic artist".[56] Mexico was a land of machismo, and Rivera, who at least outwardly refrained from the macho act that so many Mexican men preferred, was considered to be attractive by many women, who found him a man with whom one could talk to as an equal for hours.[57] The macho culture of Mexico meant that women were often seen as mere things to be "owned" by men, and at the time, Mexico had a very high rate of rape and other forms of violence against women, which made Kahlo very suspicious and fearful of machismo.[58]

Kahlo engaged in a relationship with Rivera, despite his being 42 years old, having had two common-law wives, and being a self-confessed womanizer.[59] Rivera insisted that Kahlo not wear Western clothing as he believed that Mexican women should only wear Mexican dresses, and introduced her to the Tehuana dress.[60] They were married in a civil ceremony at the town hall of Coyoacán on August 21, 1929.[61] Kahlo's parents described the union as a "marriage between an elephant and a dove", referring to the couple's differences in appearance: Rivera was tall and overweight while Kahlo was small.[62] Her mother was against the marriage, but her father approved of it because Rivera would be able to pay for Kahlo's continuing medical expenses.[63] The wedding was reported by the Mexican and international press,[64] and the marriage would be subject to constant media attention in Mexico in the coming years, with articles referring to the couple as, "Diego and Frida".[65]

Soon after the marriage, in late 1929, Kahlo and Rivera moved to Cuernavaca, where he was commissioned by American ambassador Dwight W. Morrow to paint murals for the Palace of Cortés.[66] Living in Cuernavaca sharpened Kahlo's sense of a Mexican identity as it led her to contemplate Mexico's history as she lived in a provincial city built in the Spanish style in the mostly rural Morelos state, which had seen some of the most heaviest fighting during the Mexican revolution.[67] Around the same time, she resigned her membership of the PCM in support of Rivera, who had been expelled shortly before the marriage for his support of the leftist opposite movement within the Third International.[68]

In Cuernavaca, Kahlo changed her artistic style, beginning to draw inspiration increasingly from Mexican folk art.[69] Art historian Andrea Kettenmann states that she may have been influenced by Adolfo Best Maugard's treatise on the subject, as she incorporated many of the characteristics outlined by him, for example the lack of perspective, and the combining of elements from pre-Columbian and colonial periods of Mexican art.[70] Similarly to many other Mexican women artists and intellectuals at the time,[71] Kahlo also began wearing traditional indigenous Mexican peasant clothing to emphasize her mestiza ancestry: long and colorful skirts, huipils and rebozos, elaborate headdresses and masses of jewelry.[72] She especially favored the dress of women from the allegedly matriarchal society of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, who had come to represent "an authentic and indigenous Mexican cultural heritage" in post-revolutionary Mexico.[73] The Tehuana outfit allowed Kahlo to express her feminist and anti-colonialist ideals,[74] hid her damaged body, and appealed to Rivera, who believed that "Mexican women who do not wear [Mexican clothing] ... are mentally and emotionally dependent on a foreign class to which they wish to belong".[75][d] Her identification with La Raza, the people of Mexico, and her profound interest in its culture were to remain important facets of her art throughout the rest of her life.[78]

1931–1933: Travels in the United States

After Rivera had completed the commission in Cuernavaca in late 1930, he and Kahlo moved to San Francisco, where he painted murals for the Luncheon Club of the San Francisco Stock Exchange and the California School of Fine Arts.[79] The couple was "feted, lionized, [and] spoiled" by influential collectors and clients during their stay in the city.[80] Kahlo was introduced to American artists such as Edward Weston, Ralph Stackpole, Timothy Pflueger, and Nickolas Muray.[80] Her long love affair with Muray most likely began around this time.[81]

The six months spent in San Francisco were a productive period for Kahlo,[82] who further developed the folk art style she had adopted in Cuernavaca.[83] In addition to painting portraits of several new acquaintances,[84] she made Frieda and Diego Rivera (1931), a double portrait based on their wedding photograph,[85] and The Portrait of Luther Burbank (1931), which depicted the eponymous horticulturist as a hybrid between a human and a plant.[86] Although she still publicly presented herself as simply Rivera's spouse rather than as an artist,[87] she participated for the first time in an exhibition, when Frieda and Diego Rivera was included in the Sixth Annual Exhibition of the San Francisco Society of Women Artists in the Palace of the Legion of Honor.[88][89]

Kahlo and Rivera returned to Mexico for the summer of 1931, and in the fall, traveled to New York City for the opening of Rivera's retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). In April 1932, they headed to Detroit, where he had been commissioned by the Ford Motor Company to paint murals for the Detroit Institute of Arts.[90] By this time, Kahlo had become bolder in her interactions with the press, impressing journalists with her fluency in English and stating on her arrival to the city that she was the greater artist of the two of them.[91]

The year spent in Detroit was a difficult time for Kahlo. Although she had enjoyed visiting San Francisco and New York City, she disliked aspects of American society, which she regarded as colonialist, as well as most Americans, whom she found "boring".[92]She disliked having to socialize with capitalists such as Henry and Edsel Ford, and was angered that many of the hotels in Detroit refused to accept Jewish guests.[93] In a letter to a friend, she wrote that "although I am very interested in all the industrial and mechanical development of the United States", she felt "a bit of a rage against all the rich guys here, since I have seen thousands of people in the most terrible misery without anything to eat and with no place to sleep, that is what has most impressed me here, it is terrifying to see the rich having parties day and night whiles thousands and thousands of people are dying of hunger."[94] Kahlo's time in Detroit was also complicated by a pregnancy. Her doctor agreed to perform an abortion, but the medication used was ineffective.[95] Kahlo was deeply ambivalent about having a child and had already undergone an abortion earlier in the marriage.[95]Following the failed abortion, she reluctantly agreed to continue with the pregnancy, but miscarried in July, which caused a serious hemorrhage that required her being hospitalized for two weeks.[96] Less than three months later, her mother died from complications of surgery in Mexico.[97]

Despite her dislike of Detroit and her medical problems, Kahlo's time in the city was beneficial for her artistic expression. She experimented with different techniques, such as etching and frescos,[98] and her paintings began to show a stronger narrative style.[99] She also began placing emphasis on the themes of "terror, suffering, wounds, and pain".[100] Despite the popularity of the mural in Mexican art at the time, she adopted a diametrically opposed medium, votive images or retablos, religious paintings made on small metal sheets by amateur artists to thank saints for their blessings during a calamity.[101] Amongst the works she made in the retablo manner in Detroit are Henry Ford Hospital (1932), My Birth (1932), and Self-Portrait on the Border of Mexico and United States (1932).[98] While none of Kahlo's works were featured in exhibitions in Detroit, she gave an interview to the Detroit News on her art; the article was condescendingly titled "Wife of the Master Mural Painter Gleefully Dabbles in Works of Art".[102]

Kahlo and Rivera returned to New York in March 1933, as he had been commissioned to paint a mural for the Rockefeller Center.[103] During this time, she only worked on one painting, My Dress Hangs There (1934).[103] She also gave further interviews to the American press.[103] In May, Rivera was fired from the Rockefeller Center project amid an international scandal, as he had included Vladimir Lenin in the mural and refused to change it.[104] He was instead hired to paint a mural for the New Workers School.[103]Although Rivera wished to continue their stay in the United States, Kahlo was homesick, and they returned to Mexico soon after the mural's unveiling in December 1933.[105]

1934–1939: San Ángel and international recognition

Back in Mexico City, Kahlo and Rivera moved into a new house in the wealthy neighborhood of San Ángel.[106] Commissioned from Le Corbusier's student Juan O'Gorman, it consisted of two sections joined together by a bridge; Kahlo's was painted blue and Rivera's pink and white.[107] The bohemian residence became an important meeting place for artists and political activists from Mexico and abroad.[108]

Kahlo made no new paintings in 1934, and only two in the following year.[109] She was again experiencing health problems — undergoing an appendectomy, two abortions, and the amputation of gangrenous toes[110][18]— and her marriage to Rivera had become strained. He was not happy to be back in Mexico and blamed Kahlo for their return.[111] While he had been unfaithful to her before, he now embarked on an affair with her younger sister Cristina, which deeply hurt Kahlo's feelings.[112] After finding out about it in early 1935, she moved to an apartment in central Mexico City and considered divorcing him.[113] She also had an affair of her own with American artist Isamu Noguchi.[114]

Kahlo reconciled with Rivera and Cristina later in 1935, and moved back to San Ángel.[115] She became a loving aunt to Cristina's children, Isolda and Antonio.[116] Despite the reconciliation, both Rivera and Kahlo continued their infidelities.[117] She also resumed her political activities in 1936, joining the Fourth International and becoming a founding member of a solidarity committee to provide aid the Republicans in the Spanish Civil War.[118] She and Rivera successfully petitioned the Mexican government to grant asylum to former Soviet leader Leon Trotsky, and offered La Casa Azul for him and his wife Natalia Sedova as a residence.[119] The couple lived there from January 1937 until April 1939, with Kahlo and Trotsky not only becoming good friends, but also having a brief affair.[120]

The years 1937 and 1938 were an extremely productive period for Kahlo, and she painted more "than she had done in all her eight previous years of marriage", creating such works as My Nurse and I (1937), Four Inhabitants of Mexico (1938), and What the Water Gave Me (1938).[121] Although she was still very unsure about her work, some of her paintings were exhibited in a gallery at the National Autonomous University of Mexico in early 1938.[122] She also made her first significant sale in the summer of 1938, when film star and art collector Edward G. Robinson purchased four paintings at $200 each.[122] Even greater recognition followed when French Surrealist André Breton visited Rivera in April 1938. He was impressed by Kahlo, immediately claiming her as a surrealist and describing her work as "a ribbon around a bomb".[123] He not only promised to arrange for her paintings to be exhibited in Paris, but also wrote to his friend and art dealer, Julien Levy, who invited her to hold her first solo exhibition at his gallery on the East 57th Street in Manhattan.[124]

In October, Kahlo traveled alone to New York, where her colorful Mexican dress "caused a sensation" and made her seen as "the height of exotica".[123] The exhibition opening in November was attended by famous figures such as Georgia O'Keeffe and Clare Boothe Luce, and received much positive attention in the press, although many critics adopted a condescending tone in their reviews.[125] For example, Time wrote that "Little Frida's pictures ... had the daintiness of miniatures, the vivid reds and yellows of Mexican tradition and the playfully bloody fancy of an unsentimental child".[126] Despite the Great Depression, Kahlo sold half of the twenty-five paintings presented in the exhibition.[127] She also received commissions from A. Conger Goodyear, then the president of the MoMA, and Clare Boothe Luce, for whom she painted a portrait of Luce's friend, socialite Dorothy Hale, who had committed suicide by jumping from her apartment building.[128] During the three months she spent in New York, Kahlo painted very little, instead focusing on enjoying the city to the extent that her fragile health allowed.[129] She also had several affairs, continuing the one with Nickolas Muray and also engaging in ones with Levy and Edgar Kaufmann, Jr..[130] The bisexaul Kahlo also engaged in relationships with women, which did not offend Rivera in the same way her affairs with men did.[131] Rivera considered Kahlo's relationships with women to be a sort of "safety valve" as it prevented her from engaging in affairs with men, which enraged the jealous Rivera.[132]

In January 1939, Kahlo sailed to Paris to follow up on André Breton's invitation to stage an exhibition of her work.[133] When she arrived, it turned out that he had not cleared her paintings from the customs and no longer even owned a gallery.[134] With the aid of Marcel Duchamp, she was able to arrange for the Renou et Colle Gallery to host the exhibition.[134] Further problems arose when the gallery refused to show all but two of Kahlo's paintings, considering them too shocking for audiences,[135] and Breton insisted that they be shown alongside photographs by Manuel Alvarez Bravo, pre-Columbian sculptures, eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Mexican portraits, and what she considered "junk": sugar skulls, toys, and other items he had bought from Mexican markets.[136]

The exhibition opened in March, but received much less attention than she had received in the United States, partly due to the looming Second World War, and made a loss financially, leading Kahlo to cancel a planned exhibition in London.[137] Regardless, Louvre purchased The Frame, making her the first Mexican artist to be featured in their collection.[138] She was also warmly received by other Parisian artists, such as Pablo Picasso and Joan Miró,[136] as well as the fashion world, with designer Elsa Schiaparelli designing a dress inspired by her and Vogue Paris featuring her on its pages.[137] However, her overall opinion of Paris and the Surrealists remained negative; in a letter to Muray, she called them "this bunch of coocoo lunatics and very stupid surrealists"[136] who "are so crazy 'intellectual' and rotten that I can't even stand them anymore."[139]

Kahlo sailed back to New York soon after the opening of the exhibition.[140] She was eager to be reunited with Muray, but he decided to end their affair, as he had met another woman whom he was planning to marry.[141] Kahlo traveled back to Mexico City, where Rivera requested a divorce from her. The exact reasons for his decision are unknown, but he stated publicly that it was merely a "matter of legal convenience in the style of modern times ... there are no sentimental, artistic, or economic reasons."[142] According to their friends, the divorce was mainly caused by their mutual infidelities.[143] Kahlo and Rivera were granted a divorce in November 1939, but remained friendly, with her also continuing to manage his finances and correspondence.[144]

1940–1949: La Casa Azul, success in Mexico, and declining health

Following her separation from Rivera, Kahlo moved back to La Casa Azul and threw herself into art, working from her experiences in New York and Paris, determined to earn her own living.[145] Encouraged by the recognition she was gaining as an artist, she moved from the small and more intimate tin sheets she had used since 1932 to using larger canvases, which were easier to exhibit.[146] Her technique also became more sophisticated, with motifs being less gory, she began to produce more quarter length portraits, which were easier to sell.[147] During the months following her return to Mexico, she painted several of her most famous pieces, such as The Two Fridas (1939), Self-portrait with Cropped Hair (1940), The Wounded Table (1940), and Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird (1940). Her works were featured in three exhibitions in 1940: the fourth International Surrealist Exhibition in Mexico City, the Golden Gate International Exposition in San Francisco, and Twenty Centuries of Mexican Art in MoMA in New York.[148][149]

On August 21, 1940, Trotsky was assassinated in Coyoacán, where he had continued to live after leaving La Casa Azul.[150] Kahlo was briefly suspected of being involved, as she knew the murderer, and was arrested and held for two days with her sister Cristina.[151] The following month, Kahlo traveled to San Francisco for medical treatment for back pain and a fungal infection on her hand.[152] Her continuous fragile health had been in decline since her divorce and was exacerbated by her increasingly heavy consumption of alcohol.[153] Rivera was also in San Francisco, having fled Mexico City following Trotsky's murder and working on a new mural.[154] Although she had a relationship with art dealer Heinz Berggruen during her visit to the city,[155] she and Rivera also reconciled and decided to remarry.[156] They were remarried in a simple civil ceremony in San Francisco on December 8, 1940.[157]

Kahlo and Rivera returned to Mexico soon after their remarriage, which for its first five years was less turbulent than before.[158] Both were more independent, which facilitated having extramarital love affairs.[159] La Casa Azul was their primary residence, but Rivera retained the San Ángel house for use as his studio.[160] Despite the medical treatment she had received in San Francisco, her health problems continued throughout the decade. Due to her spinal problems, she wore twenty-eight separate supportive corsets, varying from steel and leather to plaster, between 1940 and 1954.[161] She also experienced pain in her legs, while the infection on her hand had become chronic, and she also underwent treatment for syphilis.[162] The death of her father in April 1941 plunged her into a depression.[158] Her ill health made her increasingly confined to La Casa Azul, which became the center of her world in the early 1940s. She enjoyed taking care of the house and its garden, and was kept company by friends, servants, and various pets, including spider monkeys, Xoloitzcuintlis, and parrots.[163]

Kahlo's paintings continued to raise interest in the United States. In 1941, her works were featured at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, and in the following year she participated in two high-profile exhibitions in New York, the Twentieth-Century Portraits exhibition at the MoMA and the Surrealists' First Papers of Surrealism exhibition.[164] In 1943, she was included in the Mexican Art Today exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and Women Artists at Peggy Guggenheim's The Art of This Century gallery in New York.[165]

Increasingly, Kahlo also began to gain more appreciation for her art in Mexico. She became a founding member of the Seminario de Cultura Mexicana, a group of twenty-five artists commissioned by the Ministry of Public Education in 1942 to spread public knowledge of Mexican culture.[166] As a member, she took part in planning exhibitions and attended a conference on art.[167] In Mexico City, her paintings were featured in two exhibitions on Mexican art that were staged at the English-language Benjamin Franklin Library in 1943 and 1944. Further, she was invited to participate at "Salon de la Flor", an exhibition presented at the annual flower exposition.[168] An article by Rivera on Kahlo's oeuvre was also published in the journal published by the Seminario de Cultura Mexicana.[169]

Kahlo accepted a teaching position at the recently reformed, nationalistic Escuela Nacional de Pintura, Escultura y Grabado "La Esmeralda" in 1943.[170] Encouraging her students to treat her in an informal and non-hierarchical way, Kahlo's main goal was to teach them to appreciate Mexican popular culture and folk art and to derive their subjects from the streets.[171] When her health problems made it difficult for her to travel to the school in Mexico City, she began to hold her lessons at La Casa Azul.[172] Four of her students—Fanny Rabel, Arturo García Bustos, Guillermo Monroy, and Arturo Estrada—became devotees, referred as "Los Fridos" for their enthusiasm for their teacher.[173]Kahlo secured three mural commissions for herself and her students.[174] In 1944, they painted La Rosita, a pulqueria in Coyoacán. In 1945, the government commissioned them to paint murals for a Coyoacán launderette as part of a national scheme to help poor women that made their living as laundresses. The same year, the group also created murals for Posada del Sol, a hotel in Mexico City. The owner did not approve the finished work and destroyed the mural.

Despite her rising profile in Mexico, Kahlo was struggling to make a living from her art, having refused to adapt her style to suit her clients' wishes.[175] She received two commissions from the Mexican government in the early 1940s. She did not complete the first one, possibly due to her dislike of the subject, and the second commission was rejected by the commissioning body.[175] Nevertheless, she had regular private clients, such as engineer Eduardo Morillo Safa, who ordered more than thirty portraits of family members over the decade.[175] Her financial situation improved when she received a 5000-peso national prize for her painting Moses (1945) in 1946, and The Two Fridas was purchased by the Museo de Arte Moderno in 1947.[176] According to art historian Andrea Kettenmann, by the mid-1940s, her paintings were "featured in the majority of group exhibitions in Mexico." Further, Martha Zamora had written that she could "sell whatever she was currently painting; sometimes incomplete pictures were purchased right off the easel."[177]

At the same time that Kahlo was gaining recognition in her home country, her health continued to decline. By the mid-1940s, her back problems had worsened to the point that she could no longer sit or stand continuously.[178] In June, she traveled to New York for an operation in which a bone graft and a steel support were fused to her spine to straighten it.[179] The incredibly difficult operation did not result in the intended effect.[180] According to Herrera, Kahlo also sabotaged her recovery by not resting as required, and further by once physically re-opening her wounds in a fit of anger.[180] Her paintings from this period, such as Broken Column (1944), Without Hope (1945), Tree of Hope, Stand Fast (1946), and The Wounded Deer (1946), reflect her declining health.[180]

1950–1954: Last years and death

In 1950, Kahlo spent most of the year in Hospital ABC in Mexico City, where she underwent a new bone graft surgery on her spine.[181] It caused a difficult infection and necessitated several follow-up surgeries.[182] After being discharged, she was mostly confined to La Casa Azul, using a wheelchair and crutches to be ambulatory.[182] Her friends, Rivera, and her collections of objects, politics, and painting became increasingly important to her.[183]

During these final years of her life, Kahlo dedicated her time to political causes to the extent that her health allowed. She had rejoined the Mexican Communist Party in 1948,[184] and campaigned for peace by, for example, collecting signatures for the Stockholm Appeal.[185] She painted mostly still-life, portraying fruit and flowers with political symbols, such as flags or doves.[186] She was concerned about being able to portray her political convictions, stating that "until now I have managed simply an honest expression of my own self ... I must struggle with all my strength to ensure that the little positive my health allows me to do also benefits the Revolution, the only real reason to live."[184] According to Herrera, her increasing dependence on alcohol and painkillers had an effect on her paintings: her brushstrokes, previously delicate and careful, were now hastier, her use of color were more brash, and the overall style more intense and feverish.[187]

Photographer Lola Alvarez Bravo understood that Kahlo did not have much longer to live, and thus staged her first solo exhibition in Mexico at the Galería Arte Contemporaneo in April 1953.[188] Kahlo was initially not due to attend the opening, as her doctors had put her on bed rest.[188] As a solution, she ordered her four-poster bed to be moved from her home to the gallery.[188] To the surprise of the guests attending the opening, she arrived in an ambulance and was carried on a stretcher to the bed, where she stayed for the duration of the party.[188] The exhibition was not only a notable cultural event in Mexico, but also received attention in mainstream press around the world.[189] The same year, five of her paintings were also included in Tate gallery's exhibition on Mexican art in London.[190]

Kahlo's right leg was amputated at the knee due to gangrene in August 1953.[191] She became severely depressed, and after hearing that Rivera was having yet another affair, attempted suicide by overdose.[191] Her addiction to painkillers escalated, and her mood was often extremely irritable and anxious.[191] She wrote in her diary in February 1954 that "they have given me centuries of torture and at moments I almost lost my reason. I keep on wanting to kill myself. Diego is what keeps me from it, through my vain idea that he would miss me. ... But never in my life have I suffered more. I will wait a while..."[192] She was again hospitalized in April and May.[193] That spring, she resumed painting after a one-year interval.[191] Her paintings from this period include the political Marxism Will Give Health to the Sick (c. 1954) and Frida and Stalin (c. 1954), and the still-life Viva La Vida (1954).[194]

In her last days, Kahlo was mostly bedridden with bronchopneumonia, though she made a public appearance on July 2, 1954, participating with Rivera in a demonstration against the CIA invasion of Guatemala.[195] She seemed to anticipate her death, as she spoke about it to visitors and drew skeletons and angels in her diary.[196] The last drawing was a black angel, which biographer Hayden Herrera interprets as the Angel of Death.[196] It was accompanied by the last words she wrote, "I joyfully await the exit — and I hope never to return — Frida" ("Espero alegre la salida — y espero no volver jamás").[196]

The demonstration worsened her illness, and on the night of July 12, 1954, Kahlo had a high fever and was in extreme pain.[196] At approximately 6 a.m. on July 13, 1954, she was found dead in her bed by her nurse.[197] Kahlo was 47 years old. The official cause of death was pulmonary embolism, although no autopsy was performed.[196] The nurse, who counted Kahlo's painkillers to monitor her drug use, stated that Kahlo had taken an overdose the night she died. She had been prescribed a maximum dose of seven pills, but the morning she was found dead, it seemed that she had taken eleven.[198] She had also given Rivera a wedding anniversary present that evening, over a month in advance.[198] Due to these details, the lack of autopsy, her previous suicide attempt, and the contents of her diary, Herrera has argued that Kahlo had, in fact, committed suicide.[196][199]

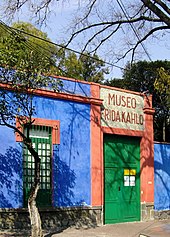

On the evening of July 13, Kahlo's body was taken to the Palacio de Bellas Artes, where it laid in state under a Communist flag.[200] The following day, it was carried to the Panteón Civil de Dolores, where friends and family attended an informal funeral ceremony. Hundreds of admirers stood outside.[200] In accordance with her wishes, Kahlo was cremated.[200] Rivera, who stated that her death was "the most tragic day of my life", died three years later in 1957.[200] He bequeathed La Casa Azul to the people of Mexico, and it was opened as a museum in 1958. Kahlo's ashes are displayed at La Casa Azul in a pre-Columbian urn.[200]

Paintings

Estimates vary on how many paintings Kahlo made during her life, with figures ranging from less than 150[201] to around 200.[202][199] Her earliest paintings, which she made in the mid-1920s, show influence from Renaissance masters and European avant-garde artists such as Amedeo Modigliani.[203] Towards the end of the decade, Kahlo began to increasingly derive her inspiration from Mexican folk art, drawn to its elements of "fantasy, naivety, and fascination with violence and death".[199] The style she developed mixed reality with surrealistic elements, and often depicted pain and death. Similarly to many other contemporary Mexican artists, Kahlo was heavily influenced by Mexicanidad, a romantic nationalism that had developed in the aftermath of the revolution.[204][199] Traditionally, in Mexico the folk culture of the common people with its fusion of Spanish and Indian elements was disparaged by the criollo (those of supposedly pure European descent) elite, who looked down upon ordinary Mexicans as being either mestizos (of mixed Spanish and Indian descent) or Indians. For an example, General Porfirio Díaz, the dictator of Mexico from 1876 to 1911 was a mestizo who spent hours every morning having make-up applied to his face to make him appear more white. Under the regime of General Díaz, Europe was the model for Mexico as Europe was "civilization" while Mexican folk culture was held in contempt.[205] After the Mexican Revolution, indigenismo started to be promoted by the state, and Kahlo embraced the folk art of the common people as a way of creating a Mexican identity that was not ashamed of its Indian heritage.[206] The Mexicanidad movement claimed to resist the "mindset of cultural inferiority" created by colonialism, and placed special importance on indigenous cultures.[207] Kahlo often embraced Mexica and Zapotec imaginary in her paintings as a sign of her commitment to indigenismo.[205] Kahlo's artistic ambition was to paint for the Mexican people, and she stated that she wished "to be worthy, with my paintings, of the people to whom I belong and to the ideas which strengthen me".[208] To enforce this image, she preferred to conceal the education she had received in art from her father and Ferdinand Fernandez and at the preparatory school. Instead, she cultivated an image of herself as a "self-taught and naive artist".[209]

When Kahlo began her career as an artist in the 1920s, the Mexican art scene was dominated by muralists. They created large public pieces in the vein of Renaissance masters and Russian socialist realists: they usually depicted masses of people and their political messages were easy to decipher.[210] Although she was close to muralists such as Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siquieros, and shared their commitment to socialism and Mexican nationalism, the majority of Kahlo's paintings were self-portraits of relatively small size.[211][199] Particularly in the 1930s, her style was especially indebted to votive paintings or retablos, which were postcard-sized religious images made by amateur artists.[212] Their purpose was to thank saints for their protection during a calamity, and they normally depicted an event, such as an illness or an accident, from which its commissioner had been saved.[213] The focus was on the figures depicted, and they seldom featured a realistic perspective or detailed background, thus distilling the event to its essentials.[214] Kahlo had an extensive collection of approximately 2,000 retablos, which she displayed on the walls of La Casa Azul.[215] According to Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen, the retablo format enabled Kahlo to "develop the limits of the purely iconic and allowed her to use narrative and allegory."[216]

Many of Kahlo's self-portraits mimic the classic bust-length portraits that were fashionable during the colonial era, but also subverted the format by depicting their subject as less attractive than in reality.[217] She began to increasingly concentrate on this format towards the end of the 1930s, thus reflecting changes in Mexican society. Increasingly disillusioned by the legacy of the revolution and struggling to cope with the effects of the Great Depression, Mexicans were abandoning the ethos of socialism for individualism.[218] This was reflected by the "personality cults", which developed around Mexican film stars such as Dolores del Rio.[218] According to Schaefer, Kahlo's "mask-like self-portraits echo the contemporaneous fascination with the cinematic close-up of feminine beauty, as well as the mystique of female otherness expressed in film noir."[218] By always repeating the same facial features, Kahlo was also drawing from the depiction of goddesses and saints in indigenous and Catholic cultures.[219]

Out of specific Mexican folk artists, Kahlo was especially influenced by Hermenegildo Bustos, whose works portrayed Mexican culture and peasant life, and José Guadalupe Posada, who depicted accidents and crime in satiric manner.[220] She also derived inspiration from the works of Hieronymus Bosch, whom she called a "man of genius", and Pieter Brueghel the Elder, whose focus on peasant life was similar to her own interest in the Mexican people.[221] Another influence was the poet Rosario Castellanos, whose poems often chronicle a woman's lot in the patriarchal Mexican society, a concern with the female body, and tell stories of immense physical and emotional pain.[206] Kahlo's paintings often feature root imagery with roots growing out of her body to tie her to the ground, reflecting in a positive sense the theme of personal growth; in a negative sense of being trapped in a particular place, time and situation; and finally in an ambiguous sense of how memories of the past influence the present for either good and/or ill.[222] In My Grandparents and I, Kahlo painted herself as a ten-year holding a ribbon that grows from an ancient tree that bears the portraits of her grandparents and other ancestors while her left foot is a tree trunk growing out of the ground, reflecting Kahlo's view of humanity's unity with the earth, and her own sense of unity with Mexico itself.[223] In Kahlo's paintings, trees serve as symbols of hope, of strength and of a continuity that transcends generations.[224] Additionally, hair features as a symbol of growth and of the feminine in Kahlo's paintings and in Self Portrait with Cropped Hair, Kahlo painted herself wearing a man's suit and shorn of her long hair, which she had just cut off.[225] Kahlo holds the scissors with one hand menacing close to her vagina, which can be interpreted as a threat to Rivera whose frequent unfaithfulness infuriated her and/or a threat to harm her own body just like she has attacked her own hair, a sign of the way that women often project their fury against others onto themselves.[226] Moreover, the picture reflects Kahlo's frustration not only with Rivera, but also her unease with the patriarchal values of Mexico as the scissors serve as a symbol of a malevolent sense of masculinity that threatens to "cut up" women, both metaphorically and literally.[226] In Mexico, the traditional Spanish values of machismo were widely embraced, and as a woman, Kahlo was always uncomfortable with machismo.[226]

As a woman who suffered for the rest of her from the bus accident that so badly injured her in her youth, Kahlo spent much of her life in hospitals and undergoing surgery, much of it performed by quacks who Kahlo naively believed could restore her back to where she had been before the accident.[223] Many of Kahlo's paintings are concerned with medical imagery, which is presented in terms of pain and hurt, featuring Kahlo bleeding and displaying her open wounds.[223] Many of Kahlo's medical paintings, especially dealing with childbirth and miscarriage, have a strong sense of guilt, of a sense of living's one life at the expense of another who has died so one might live.[224]

Although Kahlo featured herself and events from her life in her paintings, they were often more ambiguous in meaning than just depictions of her life.[227] She did not use them to simply show her subjective experience, but to raise questions about Mexican society and the construction of identity within it, particularly gender, race, and social class.[228]Historian Liza Bakewell has stated that Kahlo "recognized the conflicts brought on by revolutionary ideology":

What was it to be a Mexican? — modern, yet pre-Columbian; young, yet old; anti-Catholic yet Catholic; Western, yet New World; developing, yet underdeveloped; independent, yet colonized; mestizo, yet not Spanish nor Indian.[229]

To explore these questions through her art, Kahlo developed a complex iconography, extensively employing pre-Columbian and Christian symbols and mythology in her paintings.[230] In most of her self-portraits, she depicts her face as mask-like, but surrounded by visual cues which allow the viewer to decipher deeper meanings for it. Aztec mythology in particular features heavily in Kahlo's paintings in the form of symbols like monkeys, skeletons, skulls, blood, and hearts; often these symbols referred to the myths of Coatlicue, Quetzalcoatl, and Xolotl.[231] Other central elements that Kahlo derived from Aztec mythology were hybridity and dualism.[232] In Aztec or more correctly Mexica mythology the deities could be either male, female or could change sex as the circumstances required with for example, Xilonen, the goddess of maize turning into Centeotl, the Maize Lord over the course of the growing season before turning back into Xilonen. For the bisexual Kahlo, Mexica mythology with deities that could be either gods or goddesses depending upon the time of the year offered freedom from traditional gender roles. Many of her paintings depict opposites: life and death, pre-modernity and modernity, Mexican and European, male and female.[233]

In addition to Aztec legends, Kahlo frequently depicted three interlinked and central female figures from Mexican folklore in her paintings: La Llorona, La Chingada, and La Malinche.[234] For example, when she painted herself following her miscarriage in Detroit in Henry Ford Hospital (1932), she shows herself as weeping, with dishevelled hair and an exposed heart, which are all considered part of the appearance of La Llorona, a woman who murdered her children.[235] The painting was traditionally interpreted as simply a depiction of Kahlo's grief and pain over her failed pregnancies. But with the interpretation of the symbols in the painting and the information of Kahlo's actual views towards motherhood from her correspondence, the painting has been seen as depicting the unconventional and taboo choice of a woman remaining childless in Mexican society.

In My Dress Hangs There, painted while she was living in New York in 1933, Kahlo painted New York as a hellish place with dark colors as monstrously oversized buildings tower over insect-like masses; a decaying film poster promoting Mae West standing for the commodification of female sexuality; factories belch pollution; and a dollar sign appears in a church window.[236] In the forefront of the painting stands an empty Tehuana dress, the traditional costume of the Zapotec Indians hangs uneasily between a toilet and a golden trophy, standing not inly for Kahlo's alienation from New York, but also as a symbol of how her Mexicaniness marks out as being different in the United States.[237] In another painting, done in 1937 entitled Memory the Tehuana dress appears empty, hid in a place by red ribbon tht extents mysteriously from the sky while in the background a schoolgirl's uniform is likewise held up by a ribbon from the sky while a sad Kahlo appears in Western clothing with a hole in her chest, a rod rammed through it, and her heart, bleeding and miserable sits next to her.[238] The painting reflected in part Kahlo's sadness when she had discovered Rivera was sleeping with her sister Christina and her sense of an incomplete identity.[238] Neither Kahlo in Western clothing or Zapotec dress or her schoolgirl's uniform is complete. One of Kahlo's feet rests on the land while the other foot rests on the sea, symbolizing her mestiza identity as the land is Mexico while the sea is the Atlantic ocean over the Spanish sailed over to conquer Mexico in 1519-21.[239] The bleeding heart ripped out of its rightful place in her body also stands for the pain caused by the Spanish conquest and the attempt to "Europeanize" Mexico while the rod is a symbol of Mexico's history of political instability and violence, most recently manifested in the Mexican Revolution.[240] The weeping Kahlo stands some distance from the schoolgirl's uniform, reflecting the world of her girlhood is gone forever while she reaches out to touch the Tehuana dress, to symbolize her desire both to accept her Indian heritage and to reconcile the Spanish and Indian heritage of Mexico.[240]

Kahlo also often featured her own body in her paintings, presenting it in varying states and disguises: as wounded, broken, as a child, or clothed in different outfits, such as the Tehuana costume, a man's suit or a European dress.[241] She used her body as a metaphor to explore questions on societal roles,[242] Her paintings often depicted the female body in very unconventional manner, such as during miscarriages, and childbirth or cross-dressing.[243] In depicting the female body in graphic manner, Kahlo positioned the viewer in the role of the voyeur, "making it virtually impossible for a viewer not to assume a consciously held position in response".[244] In The Two Fridas (1939), Kahlo paints herself twice in Zapotec and a Victorian dress, through the Frida in the Victorian dress has exposed one of her breasts, showing her rejection of Victorian values for a woman while the Frida in the Zapotec dress is holding a phonograph, a product of Western technology.[240] Through the two Fridas are shown sharing the same veins connecting them, the Zapotec Frida is bleeding, suggesting a personality in intense pain.[240] The painting seems to imply that the ideal, promoted after the Revolution of a Mexico that has embraced both its Spanish and Indian heritage in the form of the mestizo is an illusion and Mexicans can only emphasize one of their heritage by slighting the other.[245] In Self-portrait on the Borderline Between the US and Mexico (1932), Kahlo paints herself standing on the U.S-Mexican border with a Coatlicue necklace, a cigarette in her mouth and a Western-style pink dress that is conservative in style, but also a see-through dress with her nipples clearly erect, symbolizing both a rebellious female sexuality that refuses to accept the traditional macho values of Mexico and her determination to be proud of being Mexican.[246] The American side of the border is a barren landscape full of huge, impersonal plant-like machines that have "roots" in the earth sucking the land dry while the Mexican side of the border is full of the ruins of the Aztec civilization amid lush vegetation, suggesting the United States is more powerful than Mexico, but also spiritually dead.[247]

Kahlo's now lost painting They Asked For Planes and Are Given Straw Wings (1938) is a commentary on her childhood and current politics.[248] As a child, Kahlo had once asked for a toy airplane, and was instead dressed with straw wings by her parents.[67] Kahlo paints herself as child reaching for the toy airplane she wanted circling in the air, which remains just of her reach while wearing her useless straw wings, clearly longing to fly, but trapped on the earth, reflecting a certain sense of loss (sentir un vacío) and broken hope.[67] The painting also refers to the Spanish Civil War, where the Spanish Republic appealed for planes from the Western powers, a request that was refused while Germany and Italy provided planes to the Spanish Nationalists.[249] In the 1930s, aviation was still a new technology as the first plane had only flown in 1903, and flying had a more romantic image then it does today.[249] For Kahlo, flight represented freedom and time travel.[249] For a woman whose life was full of physical and emotional pain, Kahlo often fantasized about the impossible hope of time travel, allowing her to go back in time to prevent various misfortunes from happening to her.[249] In Time Flies (1929), Kahlo painted a self-portrait of herself with a clock standing for time and an airplane flying in the background stands for freedom.[250] Time Flies is done in the style of the court portraits of the Spanish Habsburgs by Diego Velázquez, especially the 1652 painting Queen Mariana.[250] In evoking Velázquez, an European Old Master, Kahlo, a Mexican painter at the beginning of her career was proclaiming her intention to be his equal while also declaring her mestiza heritage as several of the objects in the Spanish style painting evoke Mexico.[250] In Times Flies, Kahlo wears an Aztec necklace whose glyph reads "beginning", a reference to her marriage to Rivera the previous year.[67] The butterfly, which goes from being an egg to a caterpillar to a pupa to a butterfly in the course of its life was an ancient Indian symbol for life, and Kahlo adopted the butterfly as a symbol for both life and freedom.[249]

According to Nancy Cooey, Kahlo made herself through her paintings into "the main character of her own mythology, as a woman, as a Mexican, and as a suffering person ... She knew how to convert each into a symbol or sign capable of expressing the enormous spiritual resistance of humanity and its splendid sexuality".[251] Similarly, Nancy Deffebach has stated that Kahlo "created herself as a subject who was female, Mexican, modern, and powerful", and who diverged from the usual dichotomy of roles of mother/whore allowed to women in Mexican society.[252] Due to her gender and divergence from the muralist tradition, Kahlo's paintings were treated as less political and more naïve and subjective than those of her male counterparts up until the late 1980s.[253] According to art historian Joan Borsa, "the critical reception of her exploration of subjectivity and personal history has all too frequently denied or de-emphasized the politics involved in examining one's own location, inheritances and social conditions [...] Critical responses continue to gloss over Kahlo's reworking of the personal, ignoring or minimizing her interrogation of sexuality, sexual difference, marginality, cultural identity, female subjectivity, politics and power."[201]

One of Kahlo's earliest champions was Surrealist artist André Breton, who claimed her as part of the movement as an artist who had supposedly developed her style "in total ignorance of the ideas that motivated the activities of my friends and myself".[254] This was echoed by Bertram D. Wolfe, who wrote that Kahlo's was a "sort of 'naïve' Surrealism, which she invented for herself".[255] Although Breton regarded her as mostly a feminine force within the Surrealist movement, Kahlo brought postcolonial questions and themes to the forefront of her brand of Surrealism.[256] While she subsequently participated in Surrealist exhibitions, she stated that she "detest[ed] Surrealism", which to her was "bourgeois art" and not "true art that the people hope from the artist".[208] Some art historians have disagreed whether her work should be classified as belonging to the movement at all. According to Andrea Kettenmann, Kahlo was a symbolist concerned more in portraying her inner experiences.[257] Emma Dexter has argued that as Kahlo derived her mix of fantasy and reality mainly from Aztec mythology and Mexican culture instead of Surrealism, it is more appropriate to consider her paintings as having more in common with magical realism, also known as New Objectivity. It also combined reality and fantasy, and employed similar style to Kahlo's, such a flattened perspective, clearly outlined characters and bright colours.[258]

Posthumous recognition and "Fridamania"

"The twenty-first-century Frida is both a star —a commercial property complete with fan clubs and merchandising— and an embodiment of the hopes and aspirations of a near-religious group of followers. This wild, hybrid Frida, a mixture of tragic bohemian, Virgin of Guadalupe, revolutionary heroine and Salma Hayek, has taken such great hold on the public imagination that it tends to obscure the historically retrievable Kahlo."[259]

The Tate Modern considers Kahlo "one of the most significant artists of the twentieth century",[260] while according to art historian Elizabeth Bakewell, she is "one of Mexico's most important twentieth-century figures".[261] Kahlo's reputation as an artist developed posthumously, as during her lifetime she was primarily known as the wife of Diego Rivera and as an eccentric personality among the international cultural elite.[262] She gradually gained more recognition in the late 1970s, when scholars began to question the exclusion of female and non-Western artists from the art historical canon, and the Chicano Movement lifted her as one of their icons.[263][264] The first two books about Kahlo were published in Mexico by Teresa del Conde and Raquel Tibol in 1976 and 1977, respectively,[265] and in 1977, The Tree of Hope Stands Firm (1944) became the first Kahlo painting to be sold in an auction, netting $19,000 at Sotheby's.[266] These milestones were followed by the first two retrospectives ever staged on Kahlo's oeuvre in 1978, one at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City and another at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago.[265]

Two events were instrumental in raising interest in her life and art for the general public outside Mexico. The first was a joint retrospective of her paintings and Tina Modotti's photographs at the Whitechapel Gallery in London, which was curated and organized by Peter Wollen and Laura Mulvey.[267] It opened in May 1982, and later traveled to Sweden, Germany, the United States, and Mexico.[268] The second was the publication of art historian Hayden Herrera's international bestseller Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo in 1983.[269][270]

By 1984, Kahlo's reputation as an artist had grown to such extent that Mexico declared her works national cultural heritage, prohibiting their export from the country.[266][271] As a result, her paintings seldom appear in international auctions and comprehensive retrospectives are rare.[271] Regardless, her paintings have still broken records for Latin American art in the 1990s and 2000s. In 1990, she became the first Latin American artist to break the one-million-dollar threshold when Diego and I was auctioned by Sotheby's for $1,430,000.[266] In 2006, Roots (1943) reached US$5.6 million,[272] and in 2016, Two Lovers in a Forest (1939) sold for $8 million.[273]

Kahlo has attracted popular interest to the extent that the term "Fridamania" has been coined to describe the phenomenon.[274] She is considered "one of the most instantly recognizable artists",[268] whose face has been "used with the same regularity, and often with a shared symbolism, as images of Che Guevara or Bob Marley".[275] Her life and art have inspired a variety of merchandise, and her distinctive look has been appropriated by the fashion world. [274][276][277] A Hollywood biopic, Julie Taymor's Frida, was also released in 2002.[278] Based on Herrera's biography and starring Salma Hayek as Kahlo, it grossed US$56 million worldwide and earned six Academy Award nominations, winning for Best Makeup and Best Original Score.[279]

Kahlo's popular appeal is seen to stem first and foremost from a fascination with her life story, especially its painful and tragic aspects. She has become an icon for several minority groups and political movements, such as feminists, the LGBTQ community, and Chicanos. Oriana Baddeley has written that Kahlo has become a signifier of non-conformity and "the archetype of a cultural minority," who is regarded simultaneously as "a victim, crippled and abused" and as "a survivor who fights back."[280] Edward Sullivan stated that Kahlo is hailed as a hero by so many because she is "someone to validate their own struggle to find their own voice and their own public personalities".[281]According to John Berger, Kahlo's popularity is partly due to the fact that "the sharing of pain is one of the essential preconditions for a refinding of dignity and hope" in twenty-first century society.[282] Kirk Varnedoe, the former chief curator of MoMA, has also stated that Kahlo's posthumous success is linked to the way in which "she clicks with today’s sensibilities—her psycho-obsessive concern with herself, her creation of a personal alternative world carries a voltage. Her constant remaking of her identity, her construction of a theater of the self are exactly what preoccupy such contemporary artists as Cindy Sherman or Kiki Smith and, on a more popular level, Madonna... She fits well with the odd, androgynous hormonal chemistry of our particular epoch."[18]

Kahlo's posthumous popularity and the commercialization of her image have drawn criticism from many scholars and cultural commenters, who think that not only have many facets of her life been mythologized, but the dramatic aspects of her biography have also overshadowed her art, producing a simplistic reading of her works in which they are reduced to literal descriptions of events in her life.[283]According to journalist Stephanie Mencimer, Kahlo "has been embraced as a poster child for every possible politically correct cause" and

"like a game of telephone, the more Kahlo's story has been told, the more it has been distorted, omitting uncomfortable details that show her to be a far more complex and flawed figure than the movies and cookbooks suggest. This elevation of the artist over the art diminishes the public understanding of Kahlo's place in history and overshadows the deeper and more disturbing truths in her work. Even more troubling, though, is that by airbrushing her biography, Kahlo's promoters have set her up for the inevitable fall so typical of women artists, that time when the contrarians will band together and take sport in shooting down her inflated image, and with it, her art."[277]

Baddeley has compared the interest in Kahlo's life to the interest in the troubled life of Vincent Van Gogh, but has also stated that a crucial difference between the two is that most people associate Van Gogh with his paintings, whereas Kahlo is usually signified by an image of herself - an intriguing commentary on the way male and female artists are regarded.[284] Similarly, Peter Wollen has compared Kahlo's cult-like following to that of Sylvia Plath, whose "unusually complex and contradictory art" has been overshadowed by simplified focus on her life.[285]

Commemorations and characterisations

Kahlo's legacy has been commemorated in several ways. La Casa Azul, her home in Coyoacán, was opened as a museum in 1958, and has become one of the most popular museums in Mexico City, with approximately 25,000 visitors monthly.[286] The city also dedicated a park, Parque Frida Kahlo, to her in Coyoacán in 1985.[287] The park features a bronze statue of Kahlo.[287] In the United States, she became the first Hispanic woman to be honored with a U.S. postage stamp in 2001,[288] and was inducted into the Legacy Walk, an outdoor public display in Chicago that celebrates the LGBT history and people, in 2012.[289]

Kahlo received several commemorations on the centenary of her birth in 2007, and some on the centenary of the birthyear she attested to, 2010. These included the Bank of Mexico releasing a new MXN$ 500-peso note, featuring Kahlo's painting titled Love's Embrace of the Universe, Earth, (Mexico), I, Diego, and Mr. Xólotl (1949) on the reverse of the note and Diego Rivera on the front,[290] It is the largest-ever retrospective of her works at Mexico City's Palacio des Bellas Artes, which broke its previous attendance record,[291]

In addition to other tributes, Kahlo's life and art have inspired artists in various fields. In 1984, Paul Leduc released a biopic, titled Frida, naturaleza viva and starring Ofelia Medina as Kahlo. She is the protagonist of three fictional novels, Barbara Mujica's Frida (2001),[292] Slavenka Drakulic's Frida's Bed (2008), and Barbara Kingsolver's The Lacuna (2009).[293] In 1994, American jazz flautist and composer James Newton released an album inspired by Kahlo, titled Suite for Frida Kahlo.[294]

Kahlo has also been the subject of several stage performances. She was the inspiration for a one-act ballet by Tamara Rojo and Annabelle Lopez Ochoa for the English National Ballet in 2016,[295] and for two operas, Robert Xavier Rodriguez's Frida, which premiered at the American Music Theater Festival in Philadelphia in 1991,[296] and Kalevi Aho's Frida y Diego, which had its premiere at the Helsinki Music Centre in Helsinki, Finland in 2014.[297] She also has been the main character in several plays, including Dolores C. Sendler's "Goodbye, My Friduchita" (1999),[298] Robert Lepage and Sophie Faucher's La Casa Azul (2002),[299]Humberto Robles' Frida Kahlo: Viva la vida! (2009),[300] and Rita Ortez Provost's Tree of Hope (2014).