- Home

- ABOUT US

- ABOUT VEYSEL BABA

- REDFOX ART HOUSE VIRTUAL TOUR

- MY LAST WILL TESTAMENT

- NOTES ON HUMANITY AND LIFE

- HUMAN BEING IS LIKE A PUZZLE WITH CONTRADICTIONS

- I HAVE A WISH ON BEHALF OF THE HUMANITY

- WE ARE VERY EXHAUSTED AS THE DOOMSDAY IS CLOSER

- NO ROAD IS LONG WITH GOOD COMPANY

- THE ROAD TO A FRIENDS HOUSE IS NEVER LONG

- MY DREAMS 1

- MY DREAMS 2

- GOLDEN WORDS ABOUT POLITICS

- GOLDEN WORDS ABOUT LOVE

- GOLDEN WORDS ABOUT LIFE

- GOLDEN WORDS ABOUT DEATH

- VEYSEL BABA ART WORKS

- SHOREDITCH PARK STORIES

- EXAMPLE LIVES

- ART GALLERY

- BOOK GALLERY

- MUSIC GALLERY

- MOVIE GALLERY

- Featured Article

- Home

- EXAMPLE LIVES

- Gustav Klimt

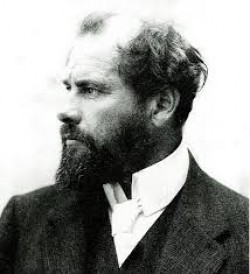

Gustav Klimt

Gustav Klimt (July 14, 1862 – February 6, 1918) was an Austrian symbolist painter and one of the most prominent members of the Vienna Secession movement. Klimt is noted for his paintings, murals, sketches, and other objets d'art. Klimt's primary subject was the female body,[1] and his works are marked by a frank eroticism.[2] In addition to his figurative works, which include allegories and portraits, he painted landscapes. Among the artists of the Vienna Secession, Klimt was the most influenced by Japanese art and its methods.

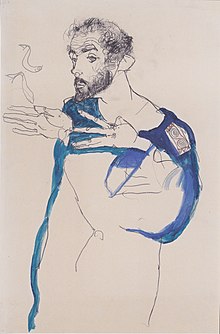

Early in his artistic career, he was a successful painter of architectural decorations in a conventional manner. As he developed a more personal style, his work was the subject of controversy that culminated when the paintings he completed around 1900 for the ceiling of the Great Hall of the University of Vienna were criticized as pornographic. He subsequently accepted no more public commissions, but achieved a new success with the paintings of his "golden phase", many of which include gold leaf. Klimt's work was an important influence on his younger contemporary Egon Schiele.

Life and work

Early life

Gustav Klimt was born in Baumgarten, near Vienna in Austria-Hungary, the second of seven children—three boys and four girls.[3] His mother, Anna Klimt (née Finster), had an unrealized ambition to be a musical performer. His father, Ernst Klimt the Elder, formerly from Bohemia, was a gold engraver.[4] All three of their sons displayed artistic talent early on. Klimt's younger brothers were Ernst Klimt and Georg Klimt.

Klimt lived in poverty while attending the Vienna School of Arts and Crafts (Kunstgewerbeschule), where he studied architectural painting until 1883.[4] He revered Vienna's foremost history painter of the time, Hans Makart. Klimt readily accepted the principles of a conservative training; his early work may be classified as academic.[4] In 1877 his brother, Ernst, who, like his father, would become an engraver, also enrolled in the school. The two brothers and their friend, Franz Matsch, began working together and by 1880 they had received numerous commissions as a team that they called the "Company of Artists". They also helped their teacher in painting murals in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.[4] Klimt began his professional career painting interior murals and ceilings in large public buildings on the Ringstraße, including a successful series of "Allegories and Emblems".

In 1888 Klimt received the Golden Order of Merit from Emperor Franz Josef I of Austria for his contributions to murals painted in the Burgtheater in Vienna.[4] He also became an honorary member of the University of Munich and the University of Vienna. In 1892 Klimt's father and brother Ernst both died, and he had to assume financial responsibility for his father's and brother's families. The tragedies also affected his artistic vision and soon he would move towards a new personal style. Characteristic of his style at the end of the 19th century is the inclusion of Nuda Veritas (naked truth) as a symbolic figure in some of his works, including Ancient Greece and Egypt (1891), Pallas Athene (1898) and Nuda Veritas (1899).[5][6] Historians believe that Klimt with the nuda veritas denounced both the policy of the Habsburgs and the Austrian society, which ignored all political and social problems of that time.[7] In the early 1890s Klimt met Austrian fashion designer Emilie Louise Flöge (a sibling of his sister-in-law) who was to be his companion until the end of his life. His painting, The Kiss (1907–08), is thought to be an image of them as lovers. He designed many costumes she created and modeled in his works.

During this period Klimt fathered at least fourteen children.[8]

Vienna secession years

Klimt became one of the founding members and president of the Wiener Sezession (Vienna Secession) in 1897 and of the group's periodical, Ver Sacrum ("Sacred Spring"). He remained with the Secession until 1908. The goals of the group were to provide exhibitions for unconventional young artists, to bring the works of the best foreign artists to Vienna, and to publish its own magazine to showcase the work of members.[9] The group declared no manifesto and did not set out to encourage any particular style—Naturalists, Realists, and Symbolists all coexisted. The government supported their efforts and gave them a lease on public land to erect an exhibition hall. The group's symbol was Pallas Athena, the Greek goddess of just causes, wisdom, and the arts—of whom Klimt painted his radical version in 1898.[10]

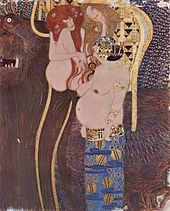

In 1894, Klimt was commissioned to create three paintings to decorate the ceiling of the Great Hall of the University of Vienna. Not completed until the turn of the century, his three paintings, Philosophy, Medicine, and Jurisprudence were criticized for their radical themes and material, and were called "pornographic".[11] Klimt had transformed traditional allegory and symbolism into a new language that was more overtly sexual and hence more disturbing to some.[11] The public outcry came from all quarters—political, aesthetic and religious. As a result, the paintings (seen in gallery below) were not displayed on the ceiling of the Great Hall. This would be the last public commission accepted by the artist.

All three paintings were destroyed by retreating SS forces in May 1945.[12][13]

His Nuda Veritas (1899) defined his bid to further "shake up" the establishment.[14] The starkly naked red-headed woman holds the mirror of truth, while above her is a quotation by Friedrich Schiller in stylized lettering, "If you cannot please everyone with your deeds and your art, please only a few. To please many is bad."[15]

In 1902, Klimt finished the Beethoven Frieze for the Fourteenth Vienna Secessionist exhibition, which was intended to be a celebration of the composer and featured a monumental polychrome sculpture by Max Klinger. Intended for the exhibition only, the frieze was painted directly on the walls with light materials. After the exhibition the painting was preserved, although it was not displayed again until 1986. The face on the Beethoven portrait resembled the composer and Vienna Court Opera director Gustav Mahler.[16]

During this period Klimt did not confine himself to public commissions. Beginning in the late 1890s he took annual summer holidays with the Flöge family on the shores of Attersee and painted many of his landscapes there. These landscapes constitute the only genre aside from figure painting that seriously interested Klimt. In recognition of his intensity, the locals called him Waldschrat ("Forest demon").[17]

Klimt's Attersee paintings are of sufficient number and quality as to merit separate appreciation. Formally, the landscapes are characterized by the same refinement of design and emphatic patterning as the figural pieces. Deep space in the Attersee works is flattened so efficiently to a single plane, that it is believed that Klimt painted them by using a telescope.[18]

Golden phase and critical success

Klimt's 'Golden Phase' was marked by positive critical reaction and financial success. Many of his paintings from this period included gold leaf. Klimt had previously used gold in his Pallas Athene (1898) and Judith I (1901), although the works most popularly associated with this period are the Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907) and The Kiss (1907–08).

Klimt travelled little, but trips to Venice and Ravenna, both famous for their beautiful mosaics, most likely inspired his gold technique and his Byzantine imagery. In 1904, he collaborated with other artists on the lavish Palais Stoclet, the home of a wealthy Belgian industrialist that was one of the grandest monuments of the Art Nouveau age. Klimt's contributions to the dining room, including both Fulfillment and Expectation, were some of his finest decorative works, and as he publicly stated, "probably the ultimate stage of my development of ornament."[19]

In 1905, Klimt created a painted portrait of Margarete Wittgenstein, Ludwig Wittgenstein's sister, on the occasion of her marriage.[20] Then, between 1907 and 1909, Klimt painted five canvases of society women wrapped in fur. His apparent love of costume is expressed in the many photographs of Flöge modeling clothing he had designed.

As he worked and relaxed in his home, Klimt normally wore sandals and a long robe with no undergarments. His simple life was somewhat cloistered, devoted to his art, family, and little else except the Secessionist Movement. He avoided café society and seldom socialized with other artists. Klimt's fame usually brought patrons to his door and he could afford to be highly selective. His painting method was very deliberate and painstaking at times and he required lengthy sittings by his subjects. Although very active sexually, he kept his affairs discreet and he avoided personal scandal.

Klimt wrote little about his vision or his methods. He wrote mostly postcards to Flöge and kept no diary. In a rare writing called "Commentary on a non-existent self-portrait", he states "I have never painted a self-portrait. I am less interested in myself as a subject for a painting than I am in other people, above all women... There is nothing special about me. I am a painter who paints day after day from morning to night... Who ever wants to know something about me... ought to look carefully at my pictures."[21]

In 1901 Herman Bahr wrote, in his Speech on Klimt: "Just as only a lover can reveal to a man what life means to him and develop its innermost significance, I feel the same about these paintings."[22]

Later life and posthumous success

In 1911 his painting Death and Life received first prize in the world exhibitions in Rome. In 1915 Anna, his mother, died. Klimt died three years later in Vienna on February 6, 1918, having suffered a stroke and pneumonia due to the worldwide influenza epidemic of that year.[23][24][25] He was buried at the Hietzinger Cemetery in Hietzing, Vienna. Numerous paintings by him were left unfinished.

Klimt's paintings have brought some of the highest prices recorded for individual works of art. In November 2003, Klimt's Landhaus am Attersee sold for $29,128,000,[26] but that sale was soon eclipsed by prices paid for other Klimts.

In 2006, the 1907 portrait, Adele Bloch-Bauer I, was purchased for the Neue Galerie New York by Ronald Lauder reportedly for US $135 million, surpassing Picasso's 1905 Boy With a Pipe (sold May 5, 2004 for $104 million), as the highest reported price ever paid for a painting.

On August 7, 2006, Christie's auction house announced it was handling the sale of the remaining four works by Klimt that were recovered by Maria Altmann and her co-heirs after their long legal battle against Austria (see Republic of Austria v. Altmann). Maria Altmann's fight to regain her family's paintings has been the subject of a number of documentary films, including Adele's Wish.[27] Her struggle also became the subject of the dramatic film the Woman in Gold, a movie inspired by Stealing Klimt, the documentary featuring Maria Altmann herself.[28] The portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer II was sold at auction in November 2006 for $88 million, the third-highest priced piece of art at auction at the time.[29][30] The Apple Tree I (ca. 1912) sold for $33 million, Birch Forest (1903) sold for $40.3 million,[31] and Houses in Unterach on Lake Atter (1916) sold for $31 million. Collectively, the five restituted paintings netted more than $327 million.[32] The painting Litzlberg am Attersee was auctioned for $40.4 million at Sotheby's in November 2011.[33]

The city of Vienna, Austria had many special exhibitions commemorating the 150th anniversary of Klimt's birth in 2012.

Folios

Gustav Klimt: Das Werk

The only folio set produced in Klimt's lifetime, Das Werk Gustav Klimts, was published initially by H. O. Miethke (of Gallerie Miethke, Klimt's exclusive gallery in Vienna) from 1908 to 1914 in an edition of 300, supervised personally by the artist. The first thirty-five editions (I-XXXV) each included an original drawing by Klimt, and the next thirty-five editions (XXXVI-LXX) each with a facsimile signature on the title page.[34] Fifty images depicting Klimt's most important paintings (1893–1913) were reproduced using collotype lithography and mounted on a heavy, cream-colored wove paper with deckled edges. Thirty-one of the images (ten of which are multicolored) are printed on Chine-collé. The remaining nineteen are high quality halftones prints. Each piece was marked with a unique signet—designed by Klimt—which was impressed into the wove paper in gold metallic ink. The prints were issued in groups of ten to subscribers, in unbound black paper folders embossed with Klimt's name. Because of the delicate nature of collotype lithography, as well as the necessity for multicolored prints (a feat difficult to reproduce with collotypes), and Klimt's own desire for perfection, the series that was published in mid-1908 was not completed until 1914.

Each of the fifty prints was categorized among five themes:

- Allegorical (which included multicolored prints of The Golden Knight, 1903 and The Virgin, c. 1912)

- Erotic-Symbolist (Water Serpents I and II, both c. 1907–08 and The Kiss, c. 1908)

- Landscapes (Farm Garden with Sunflowers, c. 1912)

- Mythical or Biblical (Pallas Athena, 1898; Judith and The Head of Holofernes, 1901; and Danaë, c. 1908)

- Portraits (Emilie Flöge, 1902)

The monochrome collotypes as well as the halftone works were printed with a variety of colored inks ranging from sepia to blue and green. Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria was the first to purchase a folio set of Das Werk Gustav Klimts in 1908.

Fünfundzwanzig Handzeichnungen

Fünfundzwanzig Handzeichnungen ("Twenty-five Drawings") was released the year after Klimt's death. Many of the drawings in the collection were erotic in nature and just as polarizing as his painted works. Published in Vienna in 1919 by Gilhofer & Ranschburg, the edition of 500 features twenty-five monochrome and two-color collotype reproductions, nearly indistinguishable from the original works. While the set was released a year after Klimt's death, some art historians suspect he was involved with production planning due to the meticulous nature of the printing (Klimt had overseen the production of the plates for Das Werk Gustav Klimts, making sure each one was to his exact specifications, a level of quality carried through similarly in Fünfundzwanzig Handzeichnungen). The first ten editions also each contained an original Klimt drawing.

Many of the works contained in this volume depict erotic scenes of nude women, some of whom are masturbating alone or are coupled in sapphic embraces.[35][36] When a number of the original drawings were exhibited to the public, at Gallerie Miethke in 1910 and the International Exhibition of Prints and Drawings in Vienna in 1913, they were met by critics and viewers who were hostile towards Klimt's contemporary perspective. There was an audience for Klimt's erotic drawings, however, and fifteen of his drawings were selected by Viennese poet Franz Blei for his translation of Hellenistic satirist Lucian's Dialogues of the Courteseans. The book, limited to 450 copies, provided Klimt the opportunity to show these more lurid depictions of women and avoided censorship thanks to an audience composed of a small group of (mostly male) affluent patrons.

Gustav Klimt An Aftermath

Composed in 1931 by editor Max Eisler and printed by the Austrian State Printing Office, Gustav Klimt An Aftermath was intended to complete the lifetime folio Das Werk Gustav Klimts. The folio contains thirty colored collotypes (fourteen of which are multicolored) and follows a similar format found in Das Werk Gustav Klimts, replacing the unique Klimt-designed signets with gold-debossed plate numbers. One hundred and fifty sets were produced in English, with twenty of them (Nos. I–XX) presented as a "gala edition" bound in gilt leather. The set contains detailed images from previously released works (Hygeia from the University Mural Medicine, 1901; a section of the third University Mural Jurisprudence, 1903), as well as the unfinished paintings (Adam and Eve, Bridal Progress).