- Home

- ABOUT US

- ABOUT VEYSEL BABA

- REDFOX ART HOUSE VIRTUAL TOUR

- MY LAST WILL TESTAMENT

- NOTES ON HUMANITY AND LIFE

- HUMAN BEING IS LIKE A PUZZLE WITH CONTRADICTIONS

- I HAVE A WISH ON BEHALF OF THE HUMANITY

- WE ARE VERY EXHAUSTED AS THE DOOMSDAY IS CLOSER

- NO ROAD IS LONG WITH GOOD COMPANY

- THE ROAD TO A FRIENDS HOUSE IS NEVER LONG

- MY DREAMS 1

- MY DREAMS 2

- GOLDEN WORDS ABOUT POLITICS

- GOLDEN WORDS ABOUT LOVE

- GOLDEN WORDS ABOUT LIFE

- GOLDEN WORDS ABOUT DEATH

- VEYSEL BABA ART WORKS

- SHOREDITCH PARK STORIES

- EXAMPLE LIVES

- ART GALLERY

- BOOK GALLERY

- MUSIC GALLERY

- MOVIE GALLERY

- Featured Article

- Home

- ART GALLERY

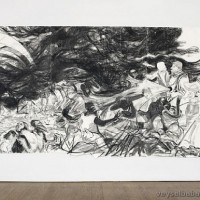

- Kara Walker

Kara Walker

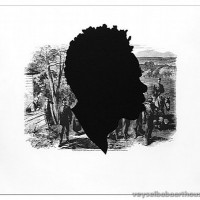

Kara Elizabeth Walker (born November 26, 1969) is an African American contemporary artist and painter who explores race, gender, sexuality, violence and identity in her work. She is best known for her room-size tableaux of black cut-paper silhouettes. Walker lives in New York City and has taught extensively at Columbia University. She is currently serving a five-year term as Tepper Chair in Visual Arts at the Mason Gross School of the Arts, Rutgers University.

Background

Walker was born in Stockton, California in 1969.[2] Her father, Larry Walker,[3] is an artist and professor.[2] Her mother worked as an administrative assistant.[4] Reflecting on her father's influence, Walker recalls: “One of my earliest memories involves sitting on my dad’s lap in his studio in the garage of our house and watching him draw. I remember thinking: ‘I want to do that, too,’ and I pretty much decided then and there at age 2½ or 3 that I was an artist just like Dad.”[5]

Walker received her BFA from the Atlanta College of Art in 1991 and her MFA from the Rhode Island School of Design in 1994.[6] Walker found herself uncomfortable and afraid to address race within her art during her early college years. However, she found her voice on this topic while attending Rhode Island School of Design for her Master's, where she began introducing race into her art. She had a distinct worry that having race as the nucleus of her content would be received as "typical" or "obvious." According to the New York Times art critic Holland Cotter, "Nothing about [Walker's] very early life would seem to have predestined her for this task. Born in 1969, she grew up in an integrated California suburb, part of a generation for whom the uplift and fervor of the civil rights movement and the want-it-now anger of Black Power were yesterday’s news."[7] Walker moved to her father's native Georgia[8] at the age of 13, when he accepted a position at Georgia State University. This was a culture shock for the young artist: "In sharp contrast with the widespread multi-cultural environment Walker had enjoyed in coastal California, Stone Mountain still held Klu Klux Klan rallies. At her new high school, Walker recalls, "I was called a 'nigger,' told I looked like a monkey, accused (I didn't know it was an accusation) of being a 'Yankee.'"[9]

Work and Career

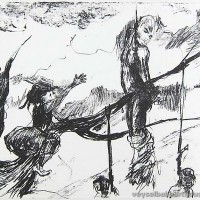

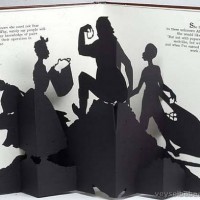

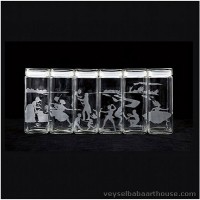

Walker is best known for her panoramic friezes of cut-paper silhouettes, usually black figures against a white wall, which address the history of American slavery and racism through violent and unsettling imagery.[10] She has also produced works in gouache, watercolor, video animation, shadow puppets, "magic-lantern" projections, as well as large-scale sculptural installations like her ambitious public exhibition with Creative Time called A Subtlety (2014). The black and white silhouettes confront the realities of history, while also using the stereotypes from the era of slavery to relate to persistent modern-day concerns.[11] Her exploration of American racism can be applied to other countries and cultures regarding relations between race and gender, and reminds us of the power of art to defy conventions.[12]

She first came to the art world's attention in 1994 with her mural Gone, An Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart. This cut-paper silhouette mural, presenting an old-timey south filled with sex and slavery was an instant hit.[13] At the age of 27, she became the second youngest recipient of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation’s “genius” grant, second only to renowned Mayanist David Stuart. In 2007, the Walker Art Center exhibition Kara Walker: My Complement, My Oppressor, My Enemy, My Love was the artist’s first full-scale U.S. museum survey. Walker currently lives in New York, where she has been a professor of visual arts in the MFA program at Columbia University since 2001.[6][8] Her influences include Adrian Piper's "who played with her identity as a light-skinned black woman to flush racism out of hiding using" [14] political self-portraits which address ostracism, otherness, racial "passing," and racism,[15] Andy Warhol, with his omnivorous eye and moral distance, and Robert Colescott, who inserted cartoonish Dixie sharecroppers into his version of Vincent van Gogh’s Dutch peasant cottages.[13]

Walker's silhouette images work to bridge unfinished folklore in the Antebellum South, raising identity and gender issues for African American women in particular. However, because of her confrontational approach to the topic, Walker's artwork is reminiscent of Andy Warhol's Pop Art during the 1960s (indeed, Walker says she adored Warhol growing up as a child).[4] Her nightmarish yet fantastical images incorporate a cinematic feel. Walker uses images from historical textbooks to show how African American slaves were depicted during Antebellum South.[4] The silhouette was typically a genteel tradition in American art history; it was often used for family portraits and book illustrations. Walker carried on this portrait tradition but used them to create characters in a nightmarish world, a world that reveals the brutality of American racism and inequality. Walker’s work pokes holes in the romantic idea of the past—exposing the humiliating, desperate reality that was life for plantation slaves. She also incorporates ominous, sharp fragments of the South’s landscape; such as Spanish moss trees and a giant moon obscured by dramatic clouds. These images surround the viewer and create a circular, claustrophobic space. This circular format paid homage to another art form, the 360-degree historical painting known as the cyclorama.[11] Some of her images are grotesque, for example, in The Battle of Atlanta, [16] a white man, presumably a Southern soldier, is raping a black girl while her brother watches in shock, a white child is about to insert his sword into a nearly-lynched black woman's vagina, and a male black slave rains tears all over an adolescent white boy. The use of physical stereotypes such as flatter profiles, bigger lips, straighter nose, and longer hair helps the viewer immediately distinguish the "negroes" from the "whities." It is blatantly clear in her artwork who is in power and who is the victim to the people with power. There is a hierarchy in America relating to race and gender with white males at the top and women of color (specifically black) at the bottom. Kara depicts the inequalities and mistreatment of African Americans by their white counterparts. Viewers at the Studio Museum in Harlem looked sickly, shocked, and some appalled upon seeing her exhibition. Thelma, the museum's chief curator, said that "throughout her career, Kara has challenged and changed the way we look at and understand American history. Her work is provocative and emotionally wrenching, yet overwhelmingly beautiful and intellectually compelling."[17] Walker has said that her work addresses the way Americans look at racism with a “soft focus,” avoiding “the confluence of disgust and desire and voluptuousness that are all wrapped up in… racism.”[11]

In an interview with New York's Museum of Modern Art, Walker stated, "I guess there was a little bit of a slight rebellion, maybe a little bit of a renegade desire that made me realize at some point in my adolescence that I really liked pictures that told stories of things- genre paintings, historical paintings- the sort of derivatives we get in contemporary society." [18]

In her piece created in 2000, Insurrection! (Our Tools Were Rudimentary, Yet We Pressed On), the silhouetted characters are against a background of colored light projections. This gives the piece a transparent quality, evocative of the production cels from the animated films of the thirties. It also references the well-known plantation story Gone With the Wind and the Technicolor film based on it. Also, the light projectors were set up so that the shadows of the viewers were also cast on the wall, making them characters and encouraging them to really assess the work’s tough themes.[11]

In 2005, she created the exhibit 8 Possible Beginnings or: The Creation of African-America, a Moving Picture, which introduced moving images and sound. This helped immerse the viewers even deeper into her dark worlds. In this exhibit, the silhouettes are used as shadow puppets. Also, she uses the voice of herself and her daughter to suggest how the heritage of early American slavery has affected her own image as an artist and woman of color.[11]

In response to Hurricane Katrina, Walker created "After the Deluge," since the hurricane had devastated many poor and black areas of New Orleans. Walker was bombarded with news images of "black corporeality," including fatalities from the hurricane reduced to bodies and nothing more. She likened these casualties to African slaves piled onto ships for the Middle Passage, the Atlantic crossing to America.[4]

In February 2009, Walker was included in the inaugural exhibition of Sacramouche Gallery, "The Practice of Joy Before Death; It Just Wouldn't Be a Party Without You." Recent works by Kara Walker include Frum Grace, Miss Pipi's Blue Tale (April–June 2011) at Lehmann Maupin, in collaboration with Sikkema Jenkins & Co. A concurrent exhibition, Dust Jackets for the Niggerati- and Supporting Dissertations, Drawings submitted ruefully by Dr. Kara E. Walker, opened at Sikkema Jenkins on the same day.[20]

Although Walker is known for her serious exhibitions with an overall deep meaning behind her work, she admits relying on "humor and viewer interaction." Walker has stated, "I didn’t want a completely passive viewer, “I wanted to make work where the viewer wouldn’t walk away; he would either giggle nervously, get pulled into history, into fiction, into something totally demeaning and possibly very beautiful.” [21]

Commissions

In 2005, The New School unveiled Walker’s first public art installation, a site-specific mural titled Event Horizon and placed along a grand stairway leading from the main lobby to a major public program space.[22]

In May 2014, Walker debuted her first sculpture, a monumental piece and public artwork entitled A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, an Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant. The massive work was installed in the derelict Domino Sugar Refinery in Brooklyn and commissioned by Creative Time. The installation consisted of a colossal female sphinx, measuring approximately 75-feet long by 35-feet high, preceded by an arrangement of fifteen life-size young male figures, dubbed attendants. The sphinx, which bore the head and features of the Mammy archetype, was made by covering a core of machine-cut blocks of polystyrene with a slurry of white sugar; Domino donated 80 tons of sugar for Walker's piece.[23] The smaller figures, modelled after racist figurines that Walker purchased online, were cast from boiled sugar (similar to hard candy) and had a dark amber or black coloring. After the exhibition closed in July 2014, the factory and the artwork were demolished as had been planned before the show.[8][24][25][26] Walker has hinted that the whiteness of the sugar references its "aesthetic, clean, and pure quality." The slave trade is highlighted in the sculpture as well. Walker also composed the "Lollipop" boys around the sphinx also made of sugar that has turned into molasses.[27] Remarking on the overwhelmingly white audience at the exhibition in tandem with the political and historical content of the installation, art critic Jamilah King argued that "the exhibit itself is a striking and incredibly well executed commentary on the historical relationship between race and capital, namely the money made off the backs of black slaves on sugar plantations throughout the Western Hemisphere. So the presence of so many white people -- and my own presence as a black woman who's a descendant of slaves -- seemed to also be part of the show."[28]

Other projects

For the season 1998/1999 in the Vienna State Opera Kara Walker designed a large scale picture (176 m2) as part of the exhibition series "Safety Curtain", conceived by museum in progress.[29] In 2009, Walker curated volume 11 of Merge Records', Score!. Invited by fellow artist Mark Bradford in 2010 to develop a set of free lesson plans for K-12 teachers at the J. Paul Getty Museum, Walker offered a lesson that had students collaborating on a story by exchanging text messages.[30]

In March, 2012 artist Clifford Owens performed a score by Kara Walker at MoMA PS1.[31]

In 2013, Walker produced 16 lithographs for a limited edition, fine art printing of the libretto Porgy & Bess, by DuBose Heyward and Ira Gershwin, published by the Arion Press.

Controversy

The Detroit Institute of Art removed her The Means to an End: A Shadow Drama in Five Acts (1995) from a 1999 exhibition "Where the Girls Are: Prints by Women from the DIA's Collection" when African-American artists and collectors protested its presence. The five-panel silhouette of an antebellum plantation scene was in the permanent collection and was to be re-exhibited at some point according to a DIA spokesperson.[32]

A Walker piece entitled The moral arc of history ideally bends towards justice but just as soon as not curves back around toward barbarism, sadism, and unrestrained chaos caused a controversy among employees at Newark Public Library who questioned in appropriateness for the reading room where it was hung. The piece was covered but not removed in December 2012.[33] After some discussion among employees and trustees the work was again revealed.[34] Kara Walker visited the New Jersey Newark Public Library to discuss the work and the controversy that went with it. Walker did not stray away from the difficult subjects such as race and history.[35] The artist Betye Saar thinks Kara's work is "revolting and negative and a form of betrayal to the slaves..[and] basically for the amusement and investment of the White art establishment." Saar voiced this on the PBS documentary I'll Make Me a World in 1999. In the summer of 1997 Saar emailed 200 fellow artists, and politicians to warn and voice her dislike and negative opinion about Kara Walker's work.[36] The protesters questioned the “negative images” (by which was meant the deprecating and regressive nature of the blackness displayed.) In their eyes, Walker’s version of blackness was a kind of “pandering, a minstrel performance dishing out unmediated stereotypes to whites.”[37]

Exhibitions

Some of Walker's exhibitions have been shown at The Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg, The Renaissance Society in Chicago, the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, and the Art Institute of Chicago. Walker’s first museum survey, in 2007, was organized by Philippe Vergne for the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis and traveled to the Whitney Museum in New York and several other cities.[8]

Selected Solo Exhibitions

- 2014: Afterword, Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York, NY.

- 2014: A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby, an Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant, Creative Time, Brooklyn, NY.[24]

- 2014: Anything but Civil: Kara Walker's Vision of the Old South, Saint Louis Art Museum.

- 2014: Emancipating the Past: Kara Walker's Tales of Slavery and Power, Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, Eugene, OR.

- 2013: Kara Walker, Camden Arts Centre.

- 2013: Kara Walker: Harper's Pictorial History of the Civil War, Pace Master Prints.

- 2013: Kara Walker: Rise Up Ye Mighty Race!, The Art Institute of Chicago.

- 2012: Kara Walker: More & more', Douglas F. Cooley Memorial Art Gallery, Reed College.

- 2011: Kara Walker: Fall Frum Grace, Miss Pipi's Blue, John Marstin, Chrystie Street.

- Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York, NY.

- 2011: Kara Walker: A Negress of Noteworthy Talent, Fondazione Merz, Torino, Italy.

- 2010: Kara Walker: Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated), Cincinnati Art Museum, OH.

- 2009: Mark Bradford, Kara Walker, Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York, NY.

- 2009: Kara Walker: Estampes, Galerie Lelong, Paris.

- 2008: Kara Walker: The Black Road, Centro de Arte Contemporáneo de Málaga, Malaga, Spain.

- 2007: Kara Walker: My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor, My Love, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN; traveled to Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Paris, France; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY; Hammer Museum, University of California, Los Angeles, CA; Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Fort Worth, TX.

- 2006: Kara Walker at the Met: After the Deluge, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY.

- 2005: Song of the South, The Roy and Edna Disney / CalArts Theater, Los Angeles, CA.

- 2004: Grub for Sharks: A Concession to the Negro Populace, Tate Liverpool, Liverpool, UK.

- 2003: Kara Walker: Narratives of a Negress, The Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, New York

- 2002: Kara Walker, Slavery!, Slavery!, 25th Bienal de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil.

- 2002: Kara Walker: Nat Turner’s Revelation (an Important Lesson from our Negro Past You Will Likely Forget To Remember), Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin, Germany

- 2002: Kara Walker: An Abbreviated Emancipation (from the Emancipation Approximation), University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor, Michigan

- 2002: Kara Walker: For the Benefit of All the Rages of Mankind, An Exhibition of Artifacts, Remnants, and Effluvia EXCAVATED from the Black Heart of a Negress, Kunstverein Hannover, Hannover, Germany

- 2001: Kara Walker, Taka Ishii Gallery, Tokyo, Japan

- 2001: American Primitive, Brent Sikkema, New York, New York

- 2001: Kara Walker: The Emancipation Approximation, A Series of Silhouette Prints, Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Tel Aviv, Israel

- 2001: Disturbing Allegories, Vanderbilt University Fine Arts Gallery, Nashville, Tennessee

- 2000: Kara Walker: Fantasies of Disbelief, Des Moines Art Center, Des Moines, Iowa

- 2000: Why I Like White Boys, an Illustrated Novel by Kara E. Walker Negress, Centre d’Art Contemporain, Geneva, Switzerland

- 1999: African’t, Galleri Index, Stockholm, Sweden

- 1999: Kara Walker: No mere words can Adequately reflect the Remorse this Negress feels at having been Cast into such a lowly state by her former Masters and so it is with a Humble heart that she so brings about their physical Ruin and earthly Demise, Capp Street Project at the Oliver Art Center, California College of Arts and Crafts, Oakland, California

- 1999: Another Fine Mess, Brent Sikkema, New York, New York

- 1999: Kara Walker, The McKinney Avenue Contemporary, Dallas, Texas

- 1998: Kara Walker, Wooster Gardens/Brent Sikkema, New York, New York

- 1998: Kara Walker, Forum for Contemporary Art, St. Louis, Missouri

- 1998: Kara Walker: Prints, The Print Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

- 1998: Opera Safety Curtain for 1998-99 Season, Vienna State Opera House, Vienna, Austria

- 1997: Kara Walker, Huntington Beach Arts Center, Huntington Beach, California

- 1997: Kara Walker: Upon My Many Masters—An Outline, The Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, California

- 1997: Presenting Negro Scenes Drawn Upon My Passage Through the South and Reconfigured for the Benefit of Enlightened Audiences Wherever Such May Be Found, by Myself, Missus K.E.B. Walker, Colored, The Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois

- 1997: May Be Found, By Myself, Missus K.E.B. Walker, Colored, The Renaissance Society at The University of Chicago, Chicago, IL.

- 1996: From the Bowels to the Bosom, Wooster Gardens/Brent Sikkema, New York, New York

- 1996: Ol’ Marster Paintin’s and Silhouette Cuttings, Bernard Toale Gallery, Boston, Massachusetts

- 1995: Look Away! Look Away! Look Away! Kara Elizabeth Walker, Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College, Annandale-on-Hudson, New York

- 1995: The Battle of Atlanta: Being the Narrative of a Negress in the Flames of Desire—A Reconstruction, Nexus Contemporary Arts Center, Atlanta, Georgia

- 1995: The High and Soft Laughter of the N***** Wenches At Night, Wooster Gardens/Brent Sikkema, New York, New York

Selected Group Exhibitions

- 2015: Represent: 200 Years of African American Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia.

- 2014: When the Stars Begin to Fall, Museum of Art, Fort Lauderdale.

- 2014: African American Art After 1950: Perspectives from the David D. Driskell Center, Figg Art Museum.

- 2014: The Intuitionists, The Drawing Center.

- 2011: Race and Representation: The African American Presence in American Art, Weatherspoon Art Museum, Greensboro, NC.

- Watch Me Move: The Animation Show, Barbican Art Gallery, London; Glenbow Museum, Calgary, Canada; Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall, Taipei, Taiwan; National Science and Technology Museum, Kaohsiung, Taiwan.

- 2010: Selections from the Hammer Contemporary Collection, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles,CA.

- In Context, Apartheid Museum (in conjunction with other venues), Johannesburg, South Africa.

- The Dissolve, Site Santa Fe Eighth International Biennial, Site Santa Fe, Santa Fe, NM.

- Abstract Resistance, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN: Feb. 27 – May 23, 2010

- Progress Reports: Art in an Era of Diversity, Invia (Institute of International Visual Arts), London, UK.

- From then to Now: Masterworks of Contemporary African American Art, Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland, OH.

- Afro Modern: Journeys through the Black Atlantic, Tate Liverpool, Liverpool, UK.; CGAC: Centro Galego de Arte Contemporánea, Santiago de Compostela, Spain.

- Brave New World, MUDAM Luxembourg, Luxembourg.

- Huckleberry Finn, CCA Wattis Institute for Contemporary Art, San Francisco, CA.

- Soaps, Flukes and Follies, Cheekwood Botanical Garden & Museum of Art, Nashville, TN.

- Cut. Scherenschnitte 1970-2010, Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg, Germany.

- 2009: Investigations of a Dog: Works from the FACE Collections, Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Turin, Italy; Ellipse Foundation, Cascais, Portugal; La maison rouge – Fondation Antoine de Galbert, Paris, France; Magasin 3 Stockholm Konsthall, Stockholm, Sweden; DESTE Foundation, Athens, Greece.

- A Guest + A Host = A Ghost: Works from the Dakis Joannou Collection. Deste Foundation for Contemporary Art, Athens, Greece.

- Between Art and Life: The Contemporary Painting and Sculpture Collection, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA.

- The Glamour Project, Lehmann Maupin, New York, NY.

- Slash: Paper Under the Knife, Museum of Art and Design, New York, NY.

- Compass in Hand: Selections from The Judith Rothschild Foundation Contemporary Drawings Collection, MoMA, New York, NY.

- America, Beirut Art Center, Beirut, Lebanon.

- Modern and Contemporary Art at Dartmouth: Highlights from the Hood Museum of Art, Hood Museum of Art, Hanover, NH.

- In Praise of Shadows, IMMA Dublin, Ireland; Istanbul Museum of Modern Art, Istanbul, Turkey; Museum Benaki, Athens,Greece.

- The Old Weird America: Folk Themes in Contemporary Art, Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, Houston TX; Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum,University of Minnesota, MN, August; de Cordova Sculpture Park and Museum, Lincoln, MA.

- Black Womanhood: Images, Icons, and Ideologies of the African Body. Hood Museum of Art, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH,; Davis Museum and Cultural Center, Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA; San Diego Museum of Art, San Diego, CA.

- Order. Desire. Light: An Exhibition of Contemporary Drawings, Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, Ireland.

- Freedom: American Sculpture, The Hague Sculpture 2008, The Hague, The Netherlands.

- Las Vegas Collects Contemporary, Las Vegas Art Museum, Las Vegas, NV.

- The Puppet Show, Institute of Contemporary Art, University of Pennsylvania; Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, TX; Frye Art Museum, Seattle, WA.

- Houston Collects: African American Art, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX.

- 2008: Cinema Remixed & Reloaded: Black Women Artists and the Moving Image since 1970, Spelman College Museum of Fine Art, Atlanta, GA; traveled to Contemporary Arts Museum Houston, Houston, TX.

- 2007: 52nd Biennale di Venezia, Venice, Italy.

- 2006: Legacies: Contemporary Artists Reflect on Slavery, New York Historical Society, New York, NY.

- 2005: The World is a Stage: Stories behind Pictures, Mori Art Museum, Tokyo, Japan.

- 2004: Nous Venons en Paix…, Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, Montreal, Canada.

- 2002: Drawing Now: Eight Propositions, The Museum of Modern Art in Queens, Queens, NY.

- 2001: Form Follows Fiction, Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea, Turin, Italy.

Collections

Among the public collections holding work by Kara Walker are the Art Institute of Chicago and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; the Baltimore Museum of Art; the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, and the Museum of Modern Art, the Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York; the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.; the Los Angeles County Museum of Art;[38] Honolulu Museum of Art; the Hickory Museum of Art, North Carolina; the Missoula Art Museum (Missoula, MT); the Seattle Art Museum; the University of Michigan Museum of Art (Ann Arbor, MI); the Weisman Art Museum (Minneapolis, MN);[39] the Musée d’art moderne Grand-Duc Jean, Luxembourg; the Tate Collection, London;[40] the The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles;,[41] the Nasher Museum at Duke University (Durham, NC), and the Menil Collection,[42] Houston.[43] Early large-scale cut-paper works have been collected by, among others, Jeffrey Deitch and Dakis Joannou.[44]

Recognition

In 1997, Walker — who was 28 at the time — was one of the youngest people to receive a MacArthur fellowship.[45] There was a lot of criticism because of her fame at such a young age and the fact that her art was most popular within the white community.[46] In 2007, Walker was listed among Time Magazine's 100 Most Influential People in The World, Artists and Entertainers, in a citation written by fellow artist Barbara Kruger.[47] In 2012, she was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[48] Walker is also the recipient of numerous grants and fellowships such as the Deutsche Bank Prize and the Larry Aldrich Award.[38] She was the United States representative for the 25th International São Paulo Biennial in Brazil (2002).[49] Walker has been featured on PBS. Her work graces the cover of musician Arto Lindsay's recording, Salt (2004).

Art market

Walker is represented by Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York. Since 2014, she has also been represented by the Victoria Miro Gallery in London.[50]

Personal life

Early in her career, Walker lived in Providence, Rhode Island with her husband, German-born jewelry professor Klaus Bürgel,[51][52] whom she married in 1996. In 1997, she gave birth to a daughter.[53] The couple has since divorced,[54] and Walker moved to New York in 2003. She maintains a studio in the Garment District, Manhattan and a country home in rural Massachusetts.[51] She has been a professor of visual arts in the MFA program at Columbia University since 2001.